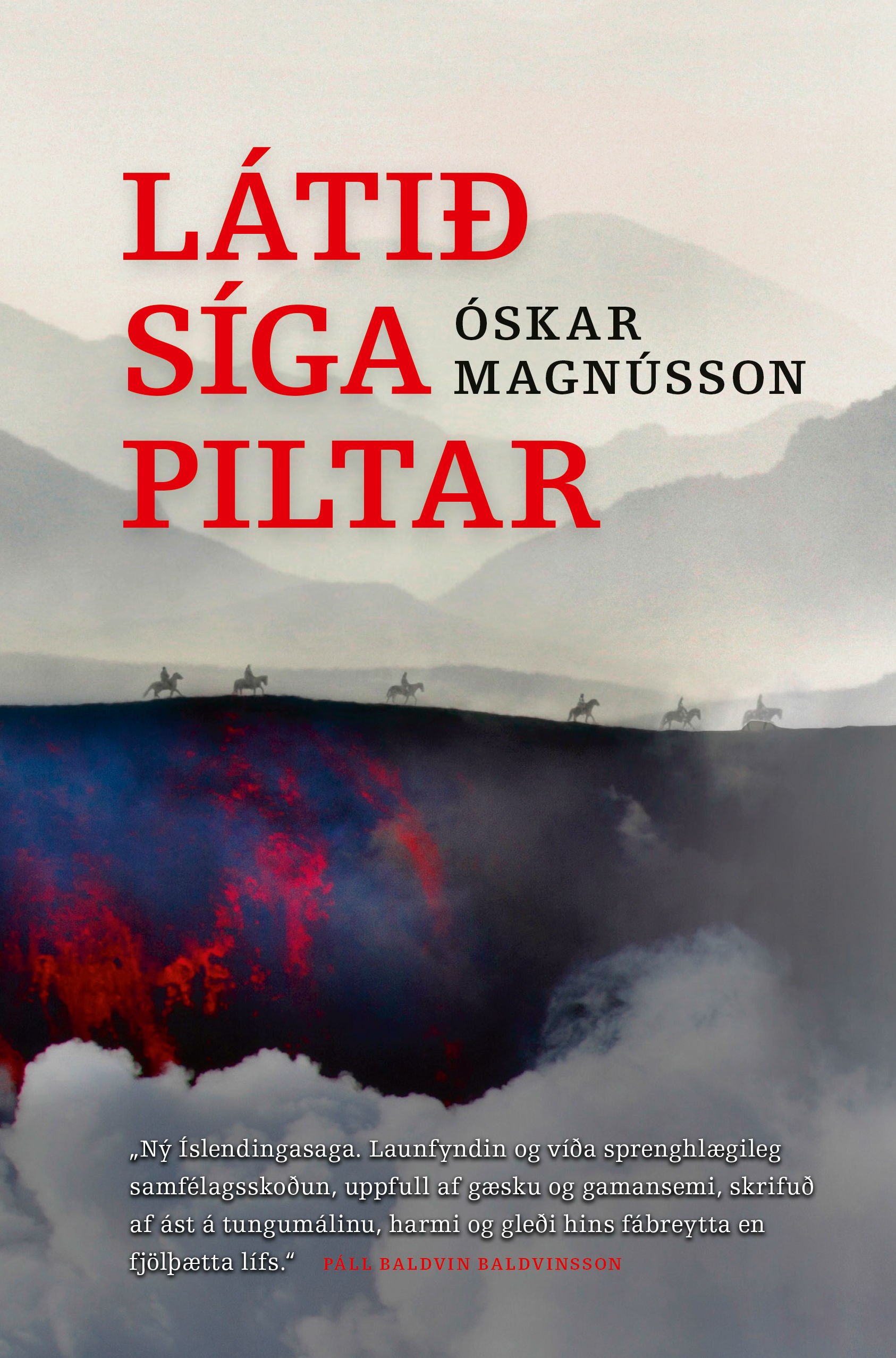

The Reckoning

Novel published with Forlagid in 2013

Excerpt

The Reckoning takes place in the present, in a secluded valley in Iceland called Hlidardalur, an oldfashioned farming community that fosters love of the land, solidarity, frugality and industriousness. When the entire valley comes under threat from natural disasters, struggle with bankers and crime, the local farmers must unite to stave off catastrophy and save the community.

Chapter from the book

There was a man was named Thormodur, whose surname was Vali. Little was known of him, and he was not honoured with lengthy sagas. He is, though, mentioned in a few stories. Vali was considered a skillful metalworker and a driven and talented weapon smith. People traveled long distances to see him, seeking weaponry which could withstand a multitude of enemies. Thormodur Vali’s weapons did not yield when faced with fierce opposition. He settled land in Hlidardalur.

Hlidardalur is wide and the land viable. Gently sloping, grassy hillsides and low hillocks in the north give the valley its name. Further east, the snow covered mountain Oddafjall is prominent, and south of there, the Hlidarfjall glacier keeps watch. The foothills give way to prairie, gravel beds and clearings where the Hlidar river has tumbled and roared through the ages, disregarding all else. Great embankments now restrain meadows and fields that have become largely overgrown.

Down the hillsides stream thousands of little waterfalls that moor gently on the lowlands and continue their journey down into the fields in rivulets. There, they collect into a clear, fresh water river which is left untroubled by the Hlidar river. This fresh water river glides over a turbulent, sandy bottom, between grassy banks and out of the valley. One of the falls is particularly impressive. It plunges over an edge, disappears momentarily and becomes visible again further down, finally cascading into a clear pool. This is Gaegju Falls. The celebrated beauty of Hlidardalur is revealed in an abundance of natural wonders.

At one time there were seven churches in Hlidardalur. Not that the people there were more religious than usual, but the valley was long, and there weren’t enough horses to transport all the valley residents. Many were obligated to walk to mass, and therefore the distance to church could not be excessive. Festive Christmas masses were the most highly attended, and at that time, everyone went to their local church. In the old tales of journeys to mass on Christmas Eve, the evening is always starlit and the moon high. Each footstep crunches on the hardened snow, and the church bells ring as people hurry in. The priest is in his most ceremonial vestments and the congregation sings together in one voice: “Today there is Joy in Sorrowful Hearts.”

Nowadays, there are only two churches left in Hlidardalur. Modern society doesn’t have the funds to support numerous churches, and each priest serves several congregations. On Christmas Eve, however, the churches are crowded and Today there is Joy is still sung. Though some things change, some stay the same.

Most farms stand proudly up in the hills and look out over the plains. Generally, the home fields are sloped – to an uncomfortable degree in some places for modern machinery, but the farmers know their land and can handle their implements skillfully. There are now a few farms where the gravel beds once were, the land grown lush after the river’s diversion. There live farmer’s daughters and sons who are descended from families throughout the valley. They have settled the land, begun farming and have had children.

The settler Thormodur Vali was said to be quite archaic in temperament and had little interest in anything other than crafting weapons. Locals in later times were not fond of him and couldn’t be bothered to find out information about the man or where his farm once stood, pointing casually into the distance when visitors would ask. Generally though, no one inquired, since few knew of Vali. Deep down, the residents of the valley were insulted that no heroes or champions had seen fit to settle in Hlidardalur and have awe-inspiring stories written in praise of them.

A forward-thinking adminstrator in the old Hlidar district many years ago had tried to make up for what residents of Hlidardalur thought most lacking in Thormodur Vali’s reputation. This administrator hired a young writer to compose a novel about the valley called The Saga of Hodur from Hlidardalur. It recalled the war stories, heroics, friendships and wisdom of men, and the treachery of women. Neighbors killed each other, farms were burned, roofs torn open, and accomplished men exiled. The narrative account was colourful and entertaining. It was easy for readers to place themselves in the character’s position and events occurred in logical, accessible locations. The book was quite good, and received fine reviews. Admittedly though, the claim that Hodur could jump three times his height in full armour was not considered entirely believable by the critics. Despite good reviews, the Hlidardalur saga was not widely distributed. It was published in the summertime, failed to get on the bestsellers list and was quickly forgotten.

Decades later, a savvy marketing man came up with the idea to make a comprehensive booklet about Hlidardalur to market the community. He wrote up a summary of the saga and had a well known artist make drawings of the characters, farms, arson attacks and other main highlights. The booklet was made available in English, German and Icelandic. A little star in the footnotes indicated in Icelandic that the material was taken from the Hlidardalur saga. More detail was not given. In a few years, the work was the main source of information about Hlidardalur. In the village, a museum was created and statues depicting the main characters of the Hlidardalur saga were set on display. By the entrance stood Hodur himself with an intimidating looking three metre long spear which was acombination of an axe, a mace, and a sledgehammer. He welcomed guests on the interactive headset that they listened to as they plodded through the exhibit. The ring of clashing weapons was heard at every other booth, while at some booths, blood squirted out of eyes, and whey came spilling out of tubs.

A steady stream of tourists began in Hlidardalur. Farmers welcomed guests to stay at their farms and built guest cabins, offered horseback riding tours and set up vendors which they named after the Hlidardalur saga. The most popular of these places, Cafe Langlokka, was named for one of the saga’s heroines, and sold coke, submarine sandwiches, cocoa and waffles. The tourism industry brought a most welcome increase in peace and contentment to the valley, and farming went on as usual: in springtime the children would harrow the fields on the old tractor. The truck came with the bags of fertilizer which were deposited at the end of the fields. The fertilizer was spread, hay was mown, raked, bound and put into bales. By mid-summer, white bales covered every field. “Tractor eggs” the teenagers called them, but the little kids pointed and said “bay hales.” The valley flourished.

Quotes

“If anything typifies the Icelandic literary tradition, it is narrative exuberance. It is boundless in Oskar Magnusson’s new book, Lower It Down, Chaps ... Oskar’s principle strength is ... sensitivity to the ironies of life.”

“A new Icelandic saga. A wry and often hilarious social commentary, brimming with compassion and humour, written with a love for language, the tragedy and comedy of the monotonous but diverse life.”

“An ironic and humorous social critique, coloured with frankness and drama. It hits home.”

“All of present Iceland forms the foundation of this novel which tells about natural catastrophes, described with artistic vigor. When Oskar Magnusson presents his first novel there are no half-measures. Here we have a cool and exciting text that will make a lot of readers happy. The conclusion: many will find it a true Icelandic magical realism.”